Is big still beautiful?

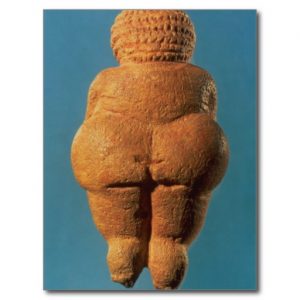

Venus did not suddenly appear in ancient Greece only to be stolen by the Romans, to be venerated by emperors as the archetypal goddess of love and sex.

Her origins were tens of millennia earlier, near enough 35,000 years ago in Northern Europe. Then she was only a handful of soft limestone with tiny feet and arms and no face. Central to her charms were ample breasts, broad hips, substantial thighs and a full belly. Her image has been found clutched in the deeply frozen hand of a long-dead solitary young hunter. She fitted happily there in his palm – warm, smooth, plumptious – a comforting epitome in his remote loneliness of all that he had loved, desired and left way back at home.

Being so tiny she travelled easily. Not much later she was to be found from Siberia to the Mediterranean coast. She had no name that we could now know – perhaps she was called “woman”.

[1]

In 1929 the English anthropologist Louis Leakey convinced himself that he had found the bones of the first homonins in the Olduvai Gorge (now in Tanzania). They proved to be 1.9 million years old: homo habilis was the very first of us.

The living remains of our earliest ancestors linger in Africa. Laurens van der Post, guru to the younger Prince Charles, described them as the “bushmen of the Kalahari” – isolated and antisocial, diminutive and derided, existing in an endless and remorseless desert, they were shot as pests for sport. Van der Post supported their cause.

We now know them as the San, a scant and pitiful population scattered along the banks of the limpid Molopo River which oozes through vast sands to mark the border between Botswana and South Africa.

The continuing existence of the San is nothing short of miraculous, you may think. But these isolated and utterly ancient hunter gatherers are not a miracle; they have been genetically groomed to store with astonishing avidity any calories extra to their immediate needs – in fat deposits around their breasts, bellies and especially their buttocks. They happily live on their humps during long and inevitable seasonal deprivations.

This trait of our earliest ancestors is scientifically termed “steatopygia”, Greek jargon for fat buttocks.

[2]

Steatopygia has evolved from an absolute necessity for survival into a desirable sign of fertility, and latterly into a signal mark of sexual attraction.

Today’s public has an obsession with the primordial attributes of those such as Jennifer Lopez and Kim Kardashian. For many young girls, imitative buttock enhancement has become the go-to plastic surgery (whilst boys are locked up if they fondle them uninvited).

[3]

40,000 years ago, when our present genetic blue print was finalised, it would have remained vital to be able to store fat as a readily available source of reserve energy. Ectomorphs, the born bean poles, have great difficulty gaining weight – muscle or fat. They would have had problems surviving during periods of famine. But endomorphs, sharing an effective storage mechanism and a slow metabolism, would have had a significant advantage – as our ancestral tribe, the San, still do.

The booming slave trade in the 17th and 18th centuries dispersed untold millions of west Africans into the Americas and the Caribbean islands to labour in the highly profitable tobacco and sugar industries. A surge of new genes flooded into the sparsely populated territories – included was steatopygia.

Today the preponderance of the genetically pre-programmed super efficient fat makers, endomorphs, is giving rise to unmanageable health problems in wealthy societies – for reasons we know all too clearly.

Unhappily obesity is fast becoming the accepted norm. The increasing financial burden of the ailing obese is unsustainable. From essential evolution to a threat to society, our plump and fertile goddess of love has developed into a symbol of overindulgence.

Whether they like it or not, pusillanimous politicians should put aside their occupational self-interest and act urgently to safeguard the endangered populations which they claim to represent.

RP

[1] – http://www.zazzle.co.uk/the_venus_of_willendorf_postcard-239492042781966158

[2] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steatopygia

[3] – http://mypersonalstyle.co.uk/the-bottom-line/