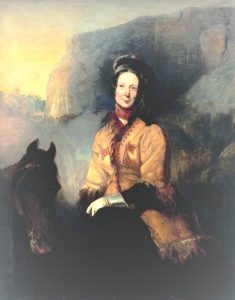

Florentia Lady Sale by Richard Thomas Bott, 1844

What remained of Napoleon on St Helena was about to be ceremoniously shipped back to France aboard the blacked-up frigate Belle-Poule – ‘Le Retour des Cendres’.

A devastated Europe had yet to reconfigure itself. In between times, ‘Great Britain’ was busy validating itself, massively fuelled by a burgeoning empire and an invigorating industrial revolution.

India was the chief source of the magic flow of gold. The Honourable East India Company, ‘The Company’, was its commercial overseer and its military guardian, accounting for half the world’s trade.

In 1828, through the terms of the Treaty of Turkmenchay with a defeated Persia, the Russian empire was perceived by an overly anxious British government as a (somewhat existential) threat to India. Easy access to India was certainly available through Persia’s border with Afghanistan, but the extreme physical obstacles of the savage mountain terrain and the polar temperature of the Hindu Kush were not fully appreciated by domestic politicians in the cossetted fastness of their Palace of Westminster. Nevertheless, the presence of a putative pro-Russian ruler on the throne of Afghanistan was deemed to be intolerable.

‘The Grand Army of the Indus’ was painstakingly assembled, and launched itself unannounced on the Islamic emirate of Dost Mohammad Khan in December 1838. A formidable force of 21,000 Company Indian troops, bolstered by some regular British battalions, advanced from the Punjab trailing 38,000 civilians and servants, 30,000 baggage camels, a large herd of cattle and a pack of foxhounds – oh, and two camels to carry one regiment’s supply of tobacco. A lightning thrust it wasn’t.

The snail-speed invasion of Afghanistan, the not-for-nothing ‘Graveyard of Empires’, was surprisingly successful, despite desperate efforts by Jihadist tribesmen to exterminate the infidel Kaffirs. A shocked Dost Mohammad promptly stood down, and the pro-British pensioner and deadly rival, the reviled Shuja Shah, was instantly re-installed on his throne in Kabul.

Job done, an improvement in Anglo-Russian diplomatic relationships and a change of government in London was seen as an ideal opportunity to reduce the extortionate expense of maintaining an extravagant military presence in remote Afghanistan to control a seemingly ragtag and bobtail mishmash of bickering philistine tribes.

Comfortable but ill-defended cantonments had been established outside the fortress walls of Kabul, and officers’ wives and families were encouraged to travel out. Life became happily normalised in these stand-alone military villages; entertainments, horse racing, gardening, theatricals, hunting, skating in winter and cricket in summer – births, deaths and marriages, zenanas for bachelors.

Florentia and Alexandrina, the wife and youngest daughter of the second-in-command of the army of occupation, Major-General Sir Robert Henry Sale, arrived to enjoy this now famously exotic environment with its super-cool summers – only to find themselves in the crux of a totally unanticipated crisis.

In the effort to contain costs, the government in India had taken the ill-judged decision to drawdown the majority of the occupying army, and to leave only a much diminished garrison in Kabul. Of significantly more importance, the monumental baksheesh paid to quell the aggressive, unpredictable and disaffected tribes of the Hindu Kush was severely cut. In particular, the Pashtun clans regarded the Khyber as strictly their own preserve.

The usual inordinate whoring and drinking habits of the British soldier at play were deeply resented by the strict Islamic residents of Kabul and the tribal chiefs. On observing the preparations for retreat, resentment rapidly became retribution.

Sir Alexander Burnes and Sir William Macnaghten, the newly knighted political agents attending the Army, had chosen to live within the walls of Kabul in preference to the distant cantonments. Burnes had made the mistake of seducing an inamorata of a local worthy: he, with his staff, were the first to be murdered by a talked-up mob. Their heads were piked on the walls. An arrogant and ill-informed Macnaghten tried to resolve the fast deteriorating situation in parley with tribal chiefs: he too perished. His mutilated body was dragged through the streets. No punishment was exacted.

During October 1841, Florentia Sale’s husband, ‘Fighting Bob’, had successfully negotiated the tortuous mountain passes to reach the relative security of the fort of Jalalabad 90 miles distant with the majority of his command intact.

On New Year’s Day 1842, now trapped in Kabul, the incompetent and ailing commander-in-chief of ‘The Grand Army of the Indus’, Major-General Sir William Elphinstone, a hero of Waterloo, agreed the Afghan rebels’ terms for the safe retirement of the remaining British colony. He agreed to leave behind his reserves of gunpowder, his new muskets and most of his cannon, and to take with him 12,000 civilians – wives, the elderly, children, servants – escorted by 700 British infantry, the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot, and 3800 Indian troops.

Florentia Sale was a perfect fit with her husband, ‘Fighting Bob’ – she had had nine children by him, variously born in Walajabad, Mauritius, France and Calcutta. As she was now the senior memsahib, she took firm charge of the British female contingent.

The utterly chaotic and ultimately fatal retreat from Kabul does not make happy reading. I am sure you already know that nobody survived the journey alive or uncaptured – except one lone horseman, Dr William Brydon, a Company assistant surgeon, seriously wounded and exhausted, who presented himself at the gate of Jalalabad on 13 January 1842, allowed, perhaps, to bear the bad news.

It had taken the Afghan people, the ragtag and bobtail, less than a fortnight to rid themselves of the repugnant Kaffirs and their effete entourage.

Prisoners were rarely taken for eminently practical reasons in a desperately poor country. The Essex boys, the 44th, out of ammunition, had fallen to a man on their last stand atop the hill at Gandamak. With no effective guardians, the remaining servants and camp followers, women and children, those who had not frozen to death, were picked off by the deadly accurate Pashtun jezail or slaughtered by the razor-sharp Khyber knife.

The concept of British invincibility had suffered a disastrous set-back, as soon evidenced by the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

The Duke of Wellington, having made his name with the Company in India, “gnawed his knuckles with frustration”.

…

Not quite all the camp followers had been summarily dispatched: Florentia Sale had been shot twice, once in the left wrist and once in the arm. A helpful passing doctor had dug the ball from her wrist: the ball in the arm she had wisely decided to keep.

Her daughter, Alexandrina, now aged 18, had married the engineer of the Kabul garrison, Lieutenant John Leigh Doyle Sturt, aged 31, less than a year earlier.

Wounded in the abdomen, Sturt was nursed by his wife and mother-in-law on a camel kajawah until he died in great pain on 9 January. His women gave him a Christian burial. Alexandrina was pregnant.

The duplicitous proxy ruler of Afghanistan, Wazir Akbar Khan, heir apparent to Dost Mohammed, intent upon the total destruction of the Kaffirs, continued to misguide and confuse the bewildered Elphinstone and his few remaining staff officers. On the day of Sturt’s burial, acting on the orders of Elphinstone, the British women, children and some wounded were herded into captivity, the purported purpose being to signal good-will in surrender negotiations and/or to remove them from the killing grounds of the mountain passes. Limping back through drifts of naked and ritually mutilated dead to Kabul, they were joined by other wounded stragglers, and, on 13 January, this small party came across General Elphinstone himself along with his staff, now held captive having been cajoled into a surrender parley by Akbar Khan.

Florentia and Alexandrina and their other co-captives were relatively well treated by Akbar Khan, being valuable negotiating assets. Elphinstone died of dysentery on 23 April. Julia Florentia Sturt was born healthy on 24 July 1842 at Kabul.

In September, the viciously vengeful and brutally competent British ‘Army of Retribution’ released the prisoners. General Sale himself freed his wife and daughter.

A year later, the now fabulously famous Florentia’s grizzled appearance on London’s social scene caused a furore. Her ‘Journal’ of the Kabul disaster had been published by John Murray (Austen, Byron, Goethe) prior to her arrival, and had had a total printing of 7,500, temporarily outselling Dickens, her highly charged celebrity becoming fleetingly as great as that of Queen Victoria herself.

Lady Sale was carefully scrutinized by her peers, and found to be “coarse” and too ready to utter oaths.

…

“It is easy to argue on the wisdom or folly of conduct after the catastrophe has taken place. With regard therefore to our chiefs, I shall only say that the Envoy has deeply paid for his attempt to out diplomatize the Afghans”.

Florentia Sale, Journal of Lady Sale, 1843

“My dear boy, as long as you do not invade Afghanistan you will be absolutely fine”.

Harold Macmillan to Alec Douglas-Home

on handing over the premiership, October 1963.

…

Fighting Bob left England in 1844 on his appointment as quartermaster-general in the Company’s wars against the Sikh empire. Born bloody-minded and bull-headed, General Sir Robert Sale was yet again wounded at a particularly vicious battle at Mudki in the Punjab. He did not survive the grapeshot to his legs. He died of his wounds on 18 December 1845, aged 63.

The widow Florentia, ‘the grenadier in petticoats’, was awarded a modest pension by Queen Victoria and a grace and favour apartment at Hampton Court Palace. Lady Sale occupied her small flat for two years before retiring to a pucca estate at Simla. She died during a trip to Cape Town for the benefit of her health on 6 July 1853, aged 62.

The monument raised by her children reads, “Beneath this stone reposes all that could die of Lady Sale…”

…

Alexandrina Sturt – “pretty but unfeeling” – married secondly Major James Garner Holmes in 1852. During the Indian Mutiny, they were both beheaded on walking out one morning by troopers of Holmes’s own regiment, the 12th Irregular Cavalry, at Segowlie, Bihar on 25 July, 1857.

Julia Florentia, now age 15, was safe in Bath with her aunt at 35 Park Street. She became the beneficiary of the will of her step-father, Major Holmes.

In 1861, age 18, Julia married Major Thomas Edmonds Mulock, age 40, at Wimborne-Minster, Dorset. Major and Mrs Mulock were immediately posted to New Zealand with the 70th (The Surrey) regiment to fight in the Māori Campaign for four years, during which they had two sons and a daughter. The now Colonel Mulock was awarded Companion of the Bath. In 1865, the family returned to England, and the 1871 census has Julia, aged 27, living with her husband, three sons, one visitor and six servants in Windlesham, Surrey.

One son, Lieutenant Edmonds Henry Mulock of the Royal Irish Fusilers was born on 14 December 1861 at Onehunga, Auckland, North Island, New Zealand. In the Egyptian War of 1882, Edmonds had fought with his regiment at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir. Two years later, at the age of 22, now stationed at Rawul Pindee, Bengal, Edmonds, whilst hunting, fired at a bear, missed, and was killed by the beast.

In 1903, his sister, Eileen Florentia, aged 39, married her widower cousin, aged 41, Henry George Bagnall Vane of the Federated Malay States Civil Service. Their son, Geoffrey was born circa 1905 in Kuala Lumpur. Eileen’s husband died on 10 March 1938 at Maia Carberry Nursing Home, Nairobi, Kenya Colony. Eileen died on 2 March 1939 in Holma, Uganda, aged 75.

…

Say farewell to the trumpets!

You will hear them no more.

But their sweet sad silvery echoes

Will call to you still

Through the half-closed door.

Jan Morris, 1926-2020

“Sir Richard Turnbull, the penultimate Governor of Aden, once told Labour politician Denis Healey that ‘when the British Empire finally sank beneath the waves of history, it would leave behind it only two monuments: one was the game of Association Football, the other was the expression “Fuck off”.’ ”

Niall Ferguson, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, 2003

References:

- Lady Sale, A Journal of the Disasters in Afghanistan 1841-2, John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1843

- Lady Sale, The First Afghan War, edited by Patrick MacRory, Longmans, 1969

- Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game, On Secret Service in High Asia, John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1990

- David Gilmour, The British in India, Three Centuries of Ambition and Experience, Allen Lane, 2018