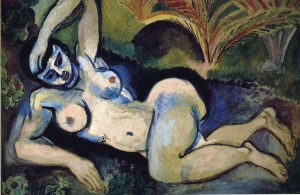

Nu Bleu : Souvenir de Biskra, Henri Matisse, 1907

Pierre and Ferdie were having a long and indulgent boys’ holiday, a pair of blasé boulevardiers escaping their tedious Paris stomping ground. In rather less restrictive Italy, they stumbled on a notorious friend: André had just returned from newly colonised Algeria. It was here, he told them in lurid detail, that he had lost the last vestiges of his virginity to a tantalising Berber dancer. Her name was Meriem.

Full of fire and lustful determination, the two friends set off to find wondrous Meriem at her home of Biskra, a remote and ancient little oasis town on the northern edge of the Sahara Desert. Cool Biskra was fast becoming an exclusive “oriental” enclave much valued by louche French avant-garde tourists for its distinctive lack of moral constraint.

At Biskra, Pierre and Ferdie had had no particular problem seeking out the talented Meriem.

“Pierre” was the Belgian born Pierre Louÿs (initially named Louis); “Ferdie” was Ferdinand Hérold; “André” was André Gide.

It was Gide, the self-confessed pederast, who later took the humbled and exiled Oscar Wilde to Biskra. Following fast behind were Lord Alfred Douglas (also with Gide), Bela Bartok, Henri Matisse, Karl Marx, Anatole France, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald…. Rudolf Valentino as “The Sheik” set off from Biskra in his most famed of roles.

Meriem’s extraordinary skills had made a profound impression on the naïve Pierre. Back in Paris and remaining truly inspired, he set about creating an antiqued version of Meriem, a pseudo-contemporary of Sappho of Lesbos, a fabricated bisexual courtesan of ancient Greece. He named her “Bilitis” whose prose poems had been purportedly found by him on the walls of a long-lost Cypriot tomb.

All clever little lies.

Stirring smidgeons of the archetypal writings of the first of all feminists, Sappho, with reworked snippets from the archaic Palatine Anthology, Pierre Louÿs carefully crafted his remarkably believable autobiography of Bilitis expressed in 143 short epigrams. Of course, “Les Chansons de Bilitis” were dedicated to MbA – Meriem ben Atala.

These clever little lies were convincing enough to briefly befuddle academic classicists – one laboriously translated a falsified epigram back into ancient Greek – much to general amusement. Publication of Les Chansons in 1894 established Louÿs as “one of the preeminent literary figures of fin-de-siècle France”.

If it had not been for the friendship between the increasingly famous author and the struggling composer, Claude Debussy, Les Chansons would, in all probability, have been lost in the mists. Debussy had turned down Louÿs’ proposal for a trip to Biskra to revisit Meriem, but he did set three of his chansons to music, an impressionistic short song cycle for soprano and piano, popular to this day – especially when expressed with sufficient sexy panache (a must watch is “Debussy: Chansons de Bilitis”, Grand Teton Music Festival, Jacqueline Stucker, on YouTube).

The French have always seemed to have been open-minded about sex, no matter which way round they happen to go. The English, well, remain buttoned up, and aggressively contentious when challenged regarding their sexual proclivities. Perhaps this has been due to the unremitting loss of French youth and intellect over the last 150 years – 12 years of the 1789 Revolution, 12 years the Napoleonic Wars, the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, and, ultimately, the desperate annihilation of The First World War.

The remnants of the fertile French population have needed to f*** hard to fill the yawning gaps. An existential point, of course, as life expectancy itself picked up sharply following the First and Second World Wars as the elderly started to live longer – and longer.

As an only child, I spent many months of holiday in France – from the ages of six to twenty, often on a beach at Juan-Les-Pins. I was frequently ennuyé, but I was taught to swim well, water ski passably, paddle my own canoe, and I devoured my books under a shady parasol. I also started to appreciate the attributes of women in their new bikinis.

Following hard on the jazzy heels of naughty Sidney Bechet, came Coccinelle, “The Lady Bug”, and her scandalous troupe from the Parisian gay club Le Carrousel, lucratively filling in time during the August low season. She was a perfectly formed little blonde chanteuse with an indecent wiggle to go with her charming prole voice. At 11am on the dot, she had a swim in the sea and a fresh water shower in the exclusive piscine of the Casino Beach. She was discreetly watched by a devoted small band of ogling older boys as she let her bikini top drop for a second or two under the squirt of the jet.

This must have been in 1959, soon after the well publicised vaginoplasty which had rocketed Coccinelle to a notorious fame. Born in 1931, more of a girl than a boy Jacques-Charles, aka “Jacqueline Charlotte”, Dufresnoy had been the first French person to have gender reassignment surgery. She had saved £3,000 of hard earned cash to travel to Casablanca where Dr Georges Burou, a French gynaecologist, could legally operate using his newly formulated technique.

Excising the male genitalia, carefully conserving the skin tissues of the penis and scrotum, Burou dilated the potential space between the rectum and the bladder through a perineal incision. Into this space, he introduced the inverted penile skin to form a vagina, the scrotum remodelled into a passable facsimile of a vulva.

This sounds a little too easy, but the complexity of the penile inversion vaginoplasty was fraught with obvious dangers, not the least being infection. In 1974, Burou first described his technique at the Symposium on Gender Dysphoria. By 1974, Burou had performed over 800 of these delicate operations.

Burou had his own strict rules: he only treated trans women who looked distinctly feminine, and he refused minors even with parental consent, as he knew that the surgery was “definitive and irreversible… and one could not risk making a mistake”.

Burou’s patients did not necessarily seek publicity, but today we might still recognise some famed names – probably April Ashley (a colleague of Coccinelle), also Jan Morris (a travel writer): these are a further two I can add to my own personal knowledge.

Still fully active, the much venerated Georges Burou died in a water skiing accident in 1987, aged 77.

In 1960 Coccinelle married publicist Francis Bonnet with the approval of the state and the Catholic Church. As she said, “the only requirement was that I had to be baptised again as Jacqueline”. Coccinelle married two further times, lastly to a transgender man, Thierry Wilson. They were together for 20 years during which they created “Devenir Femme”, a charity supporting people transitioning.

Coccinelle died in Marseille following a stroke on 9 October 2006, aged 75.

***

Albert Camus would have been happy if he had known that these two courageous Frenchmen had started to push his Sisyphus stone up the steep hill.

***

Three Songs of Bilitis

The Grotto of The Nymphs

Your little feet are daintier than those of silver Thetis. You cross your arms and press your breasts together, and rock them softly, like two snowy doves.

Beneath your hair you hide your moistened eyes, your trembling mouth and the red flowers of your ears; but naught shall stay my gentle glance or the warm breath of my kiss.

For in the secret of your body it is you, beloved Mnasidika, who hide the grotto of the nymphs which aged Homer sings, the place where the naïads weave their purple robes.

Where drop by drop the quenchless springs do flow, and from which the Northern gate permits men to descend, and where the South Gate lets Immortals enter.

Cosmetics

Everything, my life and all the world., and men, all that is not she, is naught. All that is not she, I give you, passer-by.

Does she know how many tasks I accomplish to be lovely in her eyes, tasks with my coiffure and my paints, my dresses and my perfumes?

Just so long would I tread the mill, or pull the oar or even till the soil, if these would be the price of holding her.

But never let her know these things, oh, guardian Goddesses! The very day she knows that I adore her, she’ll seek another woman.

Solitude

For whom shall I rouge my lips now? For whom shall I polish my nails? For whom perfume my hair?

For whom shall I rub my breasts with rouge, if they can no longer tempt her? For whom shall I flush my arms with milk, if they never again can hold her!

How shall I be able to sleep? How shall I get to bed? Tonight my hand, in all the bed, has not found her own warm hand.

I dare no longer enter my home, into the room, frightfully bare. I no longer dare open the door again. I never dare open my eyes.

***